| Tasty byte-size provocations to refuel your thinking! | Brought to you by: |

Music Theory in Space

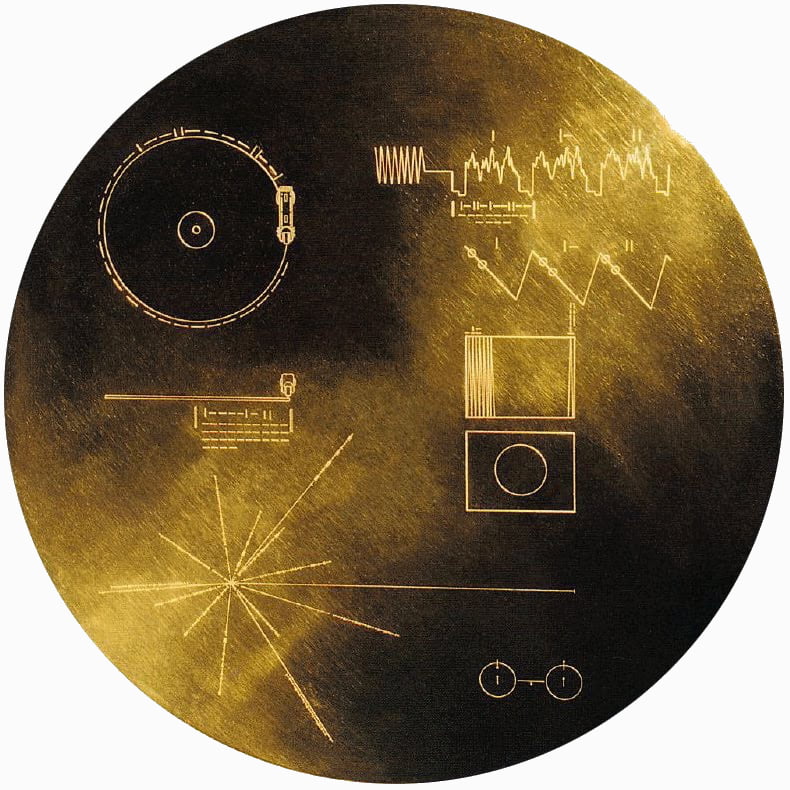

Forty years ago to this day, September 5, 1977, NASA rocketed the space probe Voyager I into space. While music theory at that time was busy circling within its own orbit exploring “the music itself,” the astronomer Carl Sagan placed on Voyager I a gold-plated disc with a selection of music ranging from J. S. Bach to Chuck Berry and rocketed human music out of Earth’s orbit in the slim hope of communicating to some extraterrestrial intelligence beyond our galaxy. The golden LP literally put a new spin on the idea of music as a “universal language.” Strangely, Sagan’s team did not include any music theory to go with NASA’s instructions for playback; there was no Heinrich Schenker for Beethoven’s Fifth, or Allen Forte for the Rite of Spring. They probably realized that such theory would have been incomprehensible to the average alien. Perhaps, they also figured out that there was no single theory capable of explaining the representative samples of music encoded on the disc. If Beethoven and Stravinsky already require different theoretical models, what would a pygmy girl’s initiation song from Zaire, panpipes from the Solomon Islands, or Louis Armstrong and his Hot Seven demand of music theory? Not only is theory inadequate to this global task, it would become increasingly disparate if it attempted to explain the diverse music on the record, resulting in a proliferation of discrete techniques. A golden textbook in several volumes would have to accompany the golden disc, ultimately alienating the alien from deciphering our music. It would be overwhelmingly incomprehensible.

The same could be said of the cultural and historical methods with which we frame music’s meaning. They would be irrelevant since music would arrive on a distant planet long after human extinction as a dislocated artifact. If an alien were to intercept the space module, it would not discover music as such but a package of “frequency-making” objects—a rotating disc etched with pits and grooves, a stylus designed to vibrate, and a set of instructions with “hieroglyphics” for setting the right frequency for playback. It would encounter music as a post-human thing, torn from the field of cultural meaning and historical reception. Our ancient technology would probably be the only surviving cultural relic of our species, floating in a distant sector of the Milky Way long after the incineration of our planet. Such music would require a “thing theory” to make sense of an obsolete humanity.

Sending music into outer space puts musicology in perspective. Has musicology been all too human? Has it been so obsessed with humanity as the heroic subject of knowledge that it has forgotten that there is a universe out there in which we are embedded as creatures along with other species? Have we narrowed what counts as music to such an extent that we no longer understand what music is? Are we just talking to ourselves, so enamored with our own universe of musicological autonomy that we already sound alien to the rest of the sciences and humanities let alone a real alien? Perhaps we need to imagine an intergalactic music theory to help us reconnect music to the rest of the universe and broaden what constitutes music. After all, music theory was the first “string theory” of the universe. It explained everything. Pythagoras would probably have called it a “big twang theory,” had his universe not been timeless and without a beginning.

So, what would a music theory for aliens be like? How would another life form begin to understand the music on the golden disc—not just the Beethoven and Stravinsky, but Senegalese percussion, rock ‘n’ roll, gamelan, and Navaho chant? What would the fundamentals of this music be, given a distant exoplanet with life forms that have evolved ears in a different planetary system? Such questions demanded by an intergalactic music theory are clearly bizarre and seemingly impractical. So why posit an extraterrestrial music theory, particularly as we are unlikely to be discussing Chuck Berry with an alien any time soon?

There are two reasons: The first reason is strategic. An intergalactic impulse should propel music theory—and musicology in general—at warp speed to the cutting edge of the humanities. Recently, the humanities have called into question the very humanity from which it derives its name. The human subject that claims to be the center of the universe is far too arrogant a being to entertain in an age where its powers have wreaked such havoc on the environment that it has inaugurated its own geological timeframe—the Anthropocene. The “post-human” turn in the humanities is, in fact, far more human than its previous incarnation, dethroning that god-like subject with a human who is more creaturely and more environmentally friendly—a reduced being, recyclable in time, reusable in nature, at one with biodegradable matter. An intergalactic music theory acknowledges the post-human and the Anthropocene . . . but it also whizzes pass them in its spacecraft, waving out of the window as if to say “Been there! Done it!” With a space-age theory, the post-human is surpassed by the extraterrestrial, and the geological outshone by the intergalactic; its time frame is measured not by millions of earth years but millions of light years. By the time some alien beams back the message “send us more Chuck Berry,” the Anthropocene may be over. The vision of an intergalactic music theory is beyond the post-human and the Anthropocene; as such it can have an epistemological impact from a perspective and scale that encompasses the science and humanities and so move beyond its own disciplinary boundaries.

The first reason, then, is strategic, repositioning the epistemological relevance of music theory; the second reason is practical, addressing the question of incomprehensibility. If we can design a theory that can explain music to an alien it should be comprehensible for humans. The alien hypothesis provides a defamiliarizing frame that enables us to rethink theory from the basics. This would be a theory that has to work at any point in our universe based on properties that we might share with an alien. It forces us to return to fundamentals of being, of physics, of time, space, and matter. It obliges us to re-evaluate what music is, particularly as any sound reproduction from Voyager’s golden LP is unlikely to sound like anything we know on earth. The differences in pressure, density, atmosphere, and evolutionary adaptation alone is enough to ensure that the second Brandenburg Concerto—the first track on the disc—is Bach . . . but not as we know it. If music theory is wide enough to encompass such redefinitions of what music is, then it might finally open up an interdisciplinary platform where music can be a shared discourse that is everywhere and for everyone . . . on earth.